How to Write a Great Merge Request

A practical guide for writing merge/pull requests that provide clarity, context, and accelerate code reviews

With a few exceptions, the history of software development is a history of teamwork. As the engineering teams consist of

individuals with different levels of knowledge, coding styles and opinions, all those differences need to be reconciled

into a homogeneous working code using various techniques. One of those techniques, code review, is a standard practice

and a crucial step to ensure that the project stays on track and progresses in the right direction. When done right,

this enables the team to move quickly and keep the high-quality code throughout the project. Code review is usually done

through a merge (sometimes called pull) request, which is a formal way to initiate merging of the changes that were done

by a developer in a team. This is usually the beginning of a discussion about the changes, review and eventually

approving and merging the said changes into the code base.

Importance of a good merge request description

There are a lot of factors that could impact this, but usually the reviewing part falls on one or two persons in a team, who are usually more senior or have a better understanding of the project. Depending on the team size, this could go south really fast, and the reviewers can get overwhelmed with merge requests quickly. What usually happens then is the worst thing that can happen to a project - reviewers start cutting corners, they see that some things could be better or clearer, but decide it’s maybe not a big deal, it will get fixed later, and potentially more glaring problems can get through, which in time makes the project unstable and creates a technical debt that will never be solved.

I usually encourage everyone to start or join the discussion on merge requests, regardless of their seniority - the more eyes on the code, the greater the chance to catch issues and fix them in time. But the final say remains with the designated code reviewer(s) that needs to approve and merge the changes. Therefore, it is imperative that they have complete context of the merge request, what was done, why it was done and what steps were taken to ensure that the integrity of the codebase remains stable.

So, why is it so important to have a good MR/PR description?

Faster Code Reviews

A good request description is paramount for efficient code reviews. It provides essential context, explaining the “why” and “what” of the changes. This saves significant time the reviewers would otherwise spend deciphering the code’s intent, searching for related tickets, or engaging in back-and-forth clarification dialogues. That Jira ticket might have all the information on the discovered bug, but it’s really not optimal for the reviewer to check the ticket, then dig through your changes to find out why your solution works and if it fits within the standards on the project. Without proper description, reviewers waste time that could be avoided with a few lines of text describing what they should look at.

If you’ve ever done code review, you know how limited the diff view can be when reviewing the changes. You can see the changed line, but it can be hard to determine if that change is really what was necessary to be done without the proper context, or if it will affect some other part of the code. That’s why the description needs to have a structure and enough information on the changes to provide this context to the reviewer, so we can all move along and continue to deliver.

Improving code quality and reducing bugs

Effective reviews depend on the reviewer understanding the change’s purpose and approach. A good description improves this understanding, enabling reviewers to identify logic errors, missed edge cases, potential security vulnerabilities, or deviations from established architectural patterns. The act of writing a description also forces the author to articulate their thought process, often leading them to catch their own mistakes or refine their approach. Catching defects during review is significantly cheaper than fixing them after the release.

Knowledge transfer and onboarding

You cannot, and should not, expect from anyone on the team to know every detail of the project, as well as every corner of the code, and anticipate how to fit the submitted changes in a large puzzle that is a complete project. When writing a MR/PR description, you transfer the part of the knowledge to the reviewer and everyone else who might be paying attention. It could be knowledge that you discovered while investigating that annoying bug, or convoluted logic behind the legacy feature. Still, whatever it is, the description can help everyone learn something that can be useful later.

Project history and audit trail

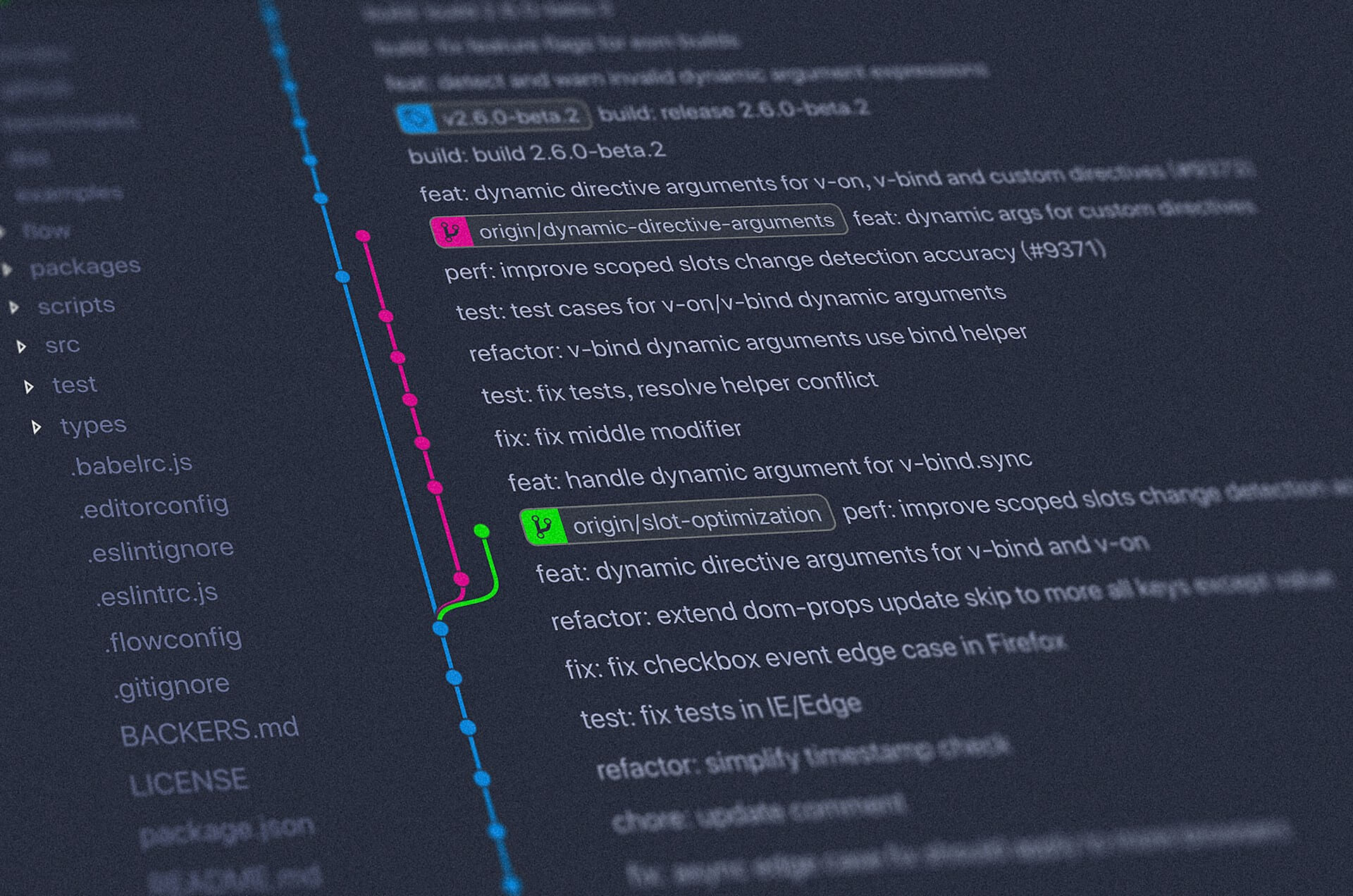

After a review, MR/PR descriptions and their associated discussion threads become a durable, searchable history of the project’s evolution. They document why specific changes were made, capturing context often lost in commit messages alone. This historical record can help future developers trying to understand legacy code, debug complex issues, perform refactoring safely, or satisfy compliance and auditing requirements.

I would argue that a good MR/PR description is more important than the commit messages, because those could get squashed and lost (which you should avoid), and are just not that valuable from my experience. The cases when you need to go through commit history are rare and the context is often lost when you have to do it. What I would recommend is keeping the same ticket code at the start of every commit and MR/PR connected to that ticket, so you can connect them later if necessary and get the context and better understanding from the merged request.

Improving team communication and collaboration

The MR/PR description is the primary communication interface for asynchronous collaboration. A clear, comprehensive description acts like a well-formed opening statement in a discussion, setting the stage for focused, constructive feedback and minimizing misunderstandings or time-consuming clarification cycles. Investing time in a good description is an act of empathy towards reviewers, respecting their time and cognitive load in tackling the difficult task of code review.

It’s all about the team

We could debate for days what makes a good merge request, but at the end of the day it’s all about what you agree on in your team. What works for one team might not work for the other. You might not be doing merge requests at all, maybe you do pair programming or Trunk-Based Development in a small team and you commit directly to main and generally like to live dangerously, or maybe each developer “owns” a part of the codebase and can commit freely whatever. Everything is fair game until everyone on the team agrees, you don’t hit any roadblocks and you don’t slowly make a pile of tech debt that will eventually come crashing down on your team. Far from it that the code review is the only way to prevent the tech debt, but it is one of the most important ones, if executed properly.

If you’re a reviewer and you catch yourself allowing the code changes without properly understanding why they were made, or because that needs to be merged quickly because QA is waiting to test the changes, it’s time to pause and think about what that could mean for a project in a few months and if it’s maybe time to review the code review strategy that you have. Request better descriptions or smaller changes, but you probably need to change something.

If you’re a developer on the team that submits the changes and waits for an approve, noticing that it takes long for a reviewer to finish changes, or you think that reviews are passing to easily, you can help your reviewer by making smaller MRs/PRs and writing better descriptions that will help navigate the changes you made.

However, as a team, you should try to find the balance between too little description and too much description. You don’t want to guess why the change was made, but you also don’t want to spend too much time writing the MR/PR.

The anatomy of a good merge request

Not counting meaningful code changes, a great merge request contains several necessary sections that explain the changes, where they were done, and why. We need to present our MR/PR as best as we can, as it’s more likely that the reviewer will be engaged and pay attention to important changes.

Title

From the top, start with a descriptive, but concise title. Try to keep it short, but to still describe the gist of the changes made. Short and non-descriptive titles should be avoided, for example, a title “Fixed a bug” could mean anything, but “Fix duplicated data fetch on a home page” gives a better idea what the MR/PR is about. Many of the teams I worked with use the ticket title as the title of the MR/PR, which is fine, as long as it serves the purpose and the reviewer knows what it’s about.

If possible, you can use a convention for titles, such as Conventional Commits, which has a following shape type-prefix(scope): description, for example fix(ui): clicking fast on a button results in duplicated orders.

If there is a Jira ticket connected to it, and there is no specific convention for titles, I like to add the ticket code to the title at the start, as it helps with tracking what was done and if you’re using Bitbucket it will connect the MR/PR to the issue automatically (maybe this works with other platforms as well, never tried it). If you’re using Conventional Commits standard for titles, skip the ticket code in title, but add it in a description body.

Links to relevant sources

Start the body of description by linking the relevant tickets, bug reports or user stories if you’re using any task tracking system. This provides the essential backstory, acceptance criteria and any prior discussion related to the work. Somebody has likely gone through the trouble of describing what needs to be done, so you should include this as soon as possible in a description. You can just paste the links to the sources or use markdown if supported to shorten the links if they are very long, so they don’t take too much space and attention.

Context (the Why)

Next, provide a clear explanation of the problem being solved, the goal being achieved, or the reason the change is necessary. This is probably the most critical element. Code shows what was changed, but only the description can effectively convey why. Without understanding the purpose, reviewers cannot properly evaluate if the proposed solution is appropriate, effective, complete, or if it affects some other part that you might not be aware of. Lack of context is the primary reason for review friction and inefficiency. This is the foundation of the entire review, so make sure to explain the business value, user impact, or technical debt being addressed. Briefly mention alternative solutions considered and justify the chosen approach if relevant.

Summary (the What)

In this section, offer a high-level overview of the changes. If applicable, mention the specific files or parts of code that were changed, to help guide the reviewer through the diff view. Use bullet points for clarity and group related changes. Explain the logic you have used or architectural decisions without merely repeating the code itself, but you can also insert relevant code snippets if necessary.

Testing evidence

Provide an overview of how you tested your changes. Did you write any tests? Did you test manually? Describe it and offer concrete details about the testing performed to verify the changes and ensure they don’t introduce regressions.

If your team doesn’t do automatic testing (we’ve all been there, it’s OK), there is a great piece of advice that was shared by one of my colleagues - provide an estimation for Risk of regression, i.e. how likely it is for your changes to introduce the regression into the working code. The exact labeling should be agreed with the team, but you can use low/medium/high labels to describe this. For example, if your MR/PR deals with changing the padding of a single element on a page, RoR is likely low, but if you’re changing a shared component used in many places, and you don’t have automatic tests in place, this is a medium or even high risk change.

Visual helpers

This is not always necessary, but if you’re dealing with visual changes, it’s not a bad idea to screenshot and attach the before and after state. You can also use animated GIFs and videos. This could help the reviewer to determine if your changes do what they are supposed to do and makes understanding of visual changes far easier. It’s one thing to see in the code that you replaced padding: 10px with padding: 1rem, but this can have a high visual impact. Don’t overdo this, though, use only when necessary and applicable.

Focus areas

In case you want the reviewer to focus on a specific area, maybe a logic that you changed or something else that can change the behavior of the system, note them in this section and help the reviewer navigate the relevant files and changes.

Other considerations

There are a few more tools that you can employ in a good merge request.

Checklist

Depending on the project you’re working on, you can add a checklist of all the necessary stuff that needs to be done before the request can be reviewed, for example:

[] - Ran build locally

[] - Existing tests pass

[] - New tests added

[] - Documentation updated

This helps reviewers to be sure that you did the tasks that are maybe not automated and significantly reduce the review cycle time and improve the quality of the outcome.

Templates

If applicable, you can take advantage of templates, most of the platforms offer these and you can set up the templates to the team's liking, and make them mandatory when submitting the merge request. They will offer a shape of the MR/PR and the team members can fill in the required sections, streamlining the process further.

What to avoid

Now that you know what to include in a merge request description, you also need to be aware of what to avoid:

- Submitting incomplete description - if you need more time to write a good description, mark the MR/PR as draft, so that the reviewers know not to look at it yet.

- Vague or uninformative titles or body - don’t force the reviewer to do all the detective work regarding context, purpose, and approach, defeating the primary goal of the description – efficient knowledge transfer.

- Simply rephrasing the code - the reviewer can see the code changes in the diff view. The description should provide a higher-level overview, the rationale, and connections, not just repeat the implementation details.

- Requiring reviewers to run code on their machines - seriously, nobody has time for that, run all the tests yourself, check the build or whatever and provide the description and testing evidence.

- Description that doesn’t match the code or functionality - the reviewer might approve something under false assumptions.

- Omitting the "why" - reviewers can't assess if the solution is appropriate if they don't understand the problem. They might approve code that solves the wrong problem or misses key requirements.

- Lack of links to supporting resources - don’t force reviewers to manually search for the related context, adding friction and interrupting their flow. Easy to link, huge time-saver for the reviewer.

Maintaining the culture of good merge requests

Establishing the habit of writing great MR/PR descriptions requires it to become an ingrained part of the team’s culture and engineering standards.

- Senior engineers and team leads should consistently model best practices by writing clear descriptions for their own MRs/PRs. Their actions set the standard for the rest of the team.

- Define and document clear expectations for MR/PR descriptions, potentially including mandatory fields or minimum information requirements.

- Make the quality of the description itself part of the code review checklist. Reviewers should feel empowered to request improvements to the description before diving deep into the code. Feedback on descriptions should be treated as seriously as feedback on the code itself.

- Offer guidance to team members, especially new hires or junior developers, on how to write effective descriptions. Provide constructive feedback during reviews, explaining why certain information is needed and share examples of good and bad descriptions.

- Automate where possible and use tools like linters or pre-commit hooks to enforce title conventions. Potentially leverage platform features for automatic linking of issues and template population.

- Continuously reinforce the importance of explaining the purpose behind the code changes. Create an environment where asking “why?” is encouraged.

The merge request description should be far more than just a formality, it should be a cornerstone of effective software development collaboration. It’s the bridge between the code author’s intent and the reviewer’s understanding, and leads to a higher code quality, and a better project history. Investing the time upfront to craft a clear, informative description, complete with context, a summary of changes, testing evidence, and potentially visual aids or specific reviewer guidance can transform the MR/PR process from a potential bottleneck into a powerful step for building better software.

Bonus - a merge request description example

## feat(ui): Add profile dropdown menu with user info and actions

**Related Issue:** [PROJ-456](https://your-jira-instance.com/browse/PROJ-456)

**Context (Why):**

Currently, users lack a quick way to view basic account information or access common actions like navigating to settings

or logging out directly from the main application header. This forces unnecessary navigation clicks, impacting user flow

efficiency.

This MR introduces a profile dropdown menu in the header to:

- Provide immediate visibility of the logged-in user (name/avatar).

- Offer quick access to key account-related actions (Profile Settings, Logout).

- Improve overall application navigation and user experience.

**Changes (What):**

This MR implements the following:

- **New Component:** Created `src/components/layout/ProfileDropdown.vue`.

- Fetches logged-in user's name and email using the existing `useUserStore()` composable.

- Displays user's avatar (using a placeholder if no avatar URL is available).

- Renders the user's full name and email address.

- Contains menu items linking to:

- `/settings/profile` (Profile Settings)

- A `logout` action (triggers the `logout` method from `useUserStore()`).

- Handles dropdown visibility state (open/close on click).

- Includes basic styling consistent with the application's theme.

- Implements a click-outside directive (`v-click-outside`) to close the dropdown when interacting elsewhere.

- **Integration:** Integrated the `ProfileDropdown` component into the main application header (

`src/components/layout/AppHeader.vue`), conditionally rendering it only when a user is authenticated.

- **Store Enhancement (Minor):** Ensured `useUserStore()` reliably exposes user `name`, `email`, and `avatarUrl`.

**Testing:**

- **Automated:**

- Added unit tests for `ProfileDropdown.vue` covering:

- Correct rendering of user name/email.

- Visibility toggling on click.

- Correct emission of logout event / triggering of store action.

- Placeholder avatar logic.

- Updated E2E tests (`tests/e2e/header.spec.ts`) to:

- Verify the dropdown appears for logged-in users.

- Check that clicking the trigger opens the dropdown panel.

- Confirm basic user info is present within the panel.

- **Manual:**

- Verified functionality across Chrome, Firefox, and Edge (latest versions).

- Tested dropdown opening/closing via trigger clicks.

- Tested dropdown closing via clicking outside the component.

- Confirmed navigation to 'Profile Settings' link works.

- Confirmed 'Logout' action successfully logs the user out and redirects appropriately.

- Checked appearance with users having long names/emails.

- Checked appearance with and without a user avatar URL.

**Visuals:**

_Before:_ (The header area previously lacked any user-specific controls)

_After:_ (The header now includes the user avatar/name trigger)

_Interaction:_ (GIF showing the dropdown opening, content, and closing)

** For Reviewers:**

- Feedback welcome on the `v-click-outside` implementation – alternative approaches considered but this seemed cleanest.

- Is pulling data directly from `useUserStore()` within `ProfileDropdown.vue` acceptable, or should `AppHeader.vue`

fetch and pass it down as props? Went with the direct approach for component encapsulation.

**Checklist:**

- [x] Code follows project style guidelines (`prettier`, `eslint`).

- [x] New component `ProfileDropdown.vue` created and integrated.

- [x] Functionality manually tested in Chrome, Firefox, Edge.

- [x] Unit tests added for the new component.

- [x] E2E tests updated for header interactions.

- [ ] Documentation updated (N/A - Internal component change).

- [x] Related Jira ticket `PROJ-456` linked.

- [x] Screenshots/GIF included for UI changes.

- [x] Considered accessibility implications (basic keyboard nav works via default browser behavior, focus management

seems okay).

Want to talk about this post? Find me on Twitter or Medium .